EN

Translate:

BOOKS TO MAKE YOU PONDER

EN

EN

Translate:

BOOKS TO MAKE YOU PONDER

EN

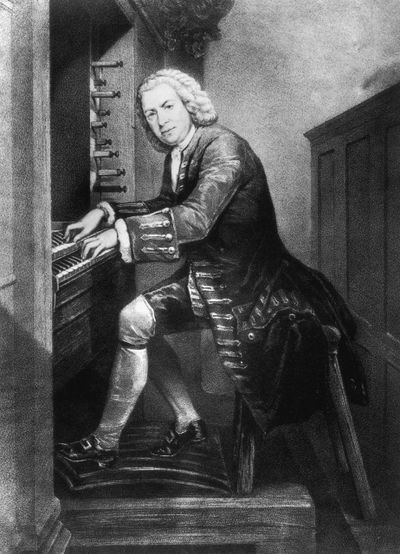

We have a rich legacy of worship from the Reformation, passed down to us through hymnody and liturgy, and later through the work of composers such as J S Bach. We look at each briefly.

It is, however, important to note that there were glimmers of light throughout history, up to the Reformation, as the Holy Spirit kept a witness to Christ alive. See, for example, a pre-Reformation hymn below.

(Image: Christianity Today.)

Luther urged that Christians participate in services, rather than be passive spectators. He wrote many hymns himself, celebrating newly-discovered truths. Perhaps the best-loved is 'Ein Feste Burg is unser Gott' which has been translated into several English versions - testament to its enduring help in worship down the centuries. Different translations include, for example: 'A safe stronghold our God is still' and 'A mighty fortress is our God'.

Luther's hymns inspired a continuing flow of hymn writing.

Thomas Cranmer brought to his writing a profound grasp of the nature of God, and of the reality of human weakness and frailty. We see the fruit of his labour perhaps most familiarly in the Book of Common Prayer. His masterly command of the English language endowed the church with a liturgy which inspired awe in the believer. The Book of Common Prayer (BCP) would be used in all Anglican churches for well over 400 years, and is still used widely. Today's service of Evensong remains as it was in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

The 'General Confession' from the BCP draws out a penitent spirit, opening the way for assurance of forgiveness. All this in the context of regular congregational worship. The BCP was for the common people, in a language they spoke (hence its name), and written in a mode which could be used over and over and over again without becoming tired or worn. For more on the BCP, see the Prayer Book Society www.pbs.org.uk.

Many evangelical churches ignore liturgy, in the belief that contemporary Christians do not connect with it. Liturgy offers a connection with the great cloud of witnesses who have run the race before us, and a sense our place in the historic line of Christian believers down the centuries.

A new book has been published to aid the pastor or praise leader in their preparation of congregational worship. It offers 26 Reformation liturgies in modern English - the most comprehensive collection available in English to date. To lead the people of God in church worship was no casual matter for the Reformers.

Liturgies from the Past for the Present (Eds: Jonathan Gibson and Mark Earngey. Foreword by Sinclair B Ferguson. New Wine Press, 2018).

Professor Henrike Lähnemann holds the Chair of Medieval German and Linguistics at Oxford. She is a Fellow of St Edmund Hall.

A major theme of her work has been to engage with the Reformation. As well as overseeing unique translations of Luther's writing, she has collaborated closely with the Oxford Bach Soloists as they have explored and performed Bach's Reformation music. Here, Prof Lähnemann gives the background to the contribution of Bach's Reformation legacy.

The Augsburg Confession (setting out Lutheran theology) was presented to the Holy Roman Emperor on 25 June 1530. This was seen as a key document, having been incorporated into the so-called Book of Concord which reconciled several strains of reformed Christianity.

Bach was examined on its content, and had to sign a statement of his adherence to it, as a condition of his employment as a church musician in Leipzig,

The two hundredth anniversary of the Confession

The two hundredth anniversary of the Confession, in 1730, was observed in Leipzig with three days of religious celebration, putting it on par with Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost – the principal feasts of the year. Bach performed a cantata on each of the three days: ‘Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied’ BWV 190a (‘Sing to the Lord a new song’), ‘Gott, man lobet dich in der Stille zu Sion’ BWV 120b (‘God you are praised in the stillness of Zion’), and ‘Wünschet Jerusalem Glück’ BWV Anh. 4a (‘Pray for the peace of Jerusalem’).

Complete printed texts for these works survive but no musical sources, though some of the music is known from Bach’s use of it in other works. Another famous piece connected to the Augsburg Confession is Felix Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony, composed for the tercentennial in 1830 and quoting Luther’s best known hymn, ‘Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott’ (‘A mighty fortress is our God’).

One of the earliest printings of that hymn is found in Geistliche Lieder zu Wittemberg (Wittenberg: Josef Klug, 1544), CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 via Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin/Preussischer Kulturbesitz.

The two-hundredth anniversary of Luther's theses

1717 marked the two hundredth anniversary of the most famous Reformation event of all – the appearance of Martin Luther’s Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, an academic and theological position paper on the nature of repentance. Luther’s nailing of his 95 theses on the topic to the Wittenberg church door has been elevated in popular church history to the defining moment of the start of the Reformation. Modern scholarship tends to understand this as being more like a posting on a bulletin board than an act of defiance. (There’s a book of popular history called The Reformation: How a Monk and a Mallet Changed the World). But this event took on a symbolic role as the beginning of the Lutheran Reformation.

In 1717 Bach was in the last months of his employment at the court of Weimar, where the reigning Duke arranged elaborate commemorations. There is no indication that Bach composed any of the music marking the occasion, perhaps because relations with his employer were fraying. Bach had received an offer for a more prestigious and better-paying job elsewhere, and the tone of his demand for release led to his month-long imprisonment just a few days after the Reformation bicentennial.

The 150th anniversary onwards

From 1667, the 150th anniversary of Luther's posting of his theses, 31 October has been celebrated each year as Reformation Day with a special liturgy throughout Lutheran lands. Bach composed two cantatas for the occasion: ‘Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott’ BWV 80, possibly as early as 1724; and ‘Gott, der Herr, ist Sonn und Schild’ BWV 79 (‘God, the Lord, is sun and shield’) in 1725. A third cantata may also have been used: the first part of ‘Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes’ BWV 76 (‘The heavens tell the glory of God’), originally for a different time of the church year.

It is not certain whether the Reformation Day use of this piece began under Bach or after his lifetime. But whoever adapted it recognized a connection between its opening text from Psalm 19 (‘The heavens tell the glory of God, and the skies proclaim the work of his hands; there is no speech nor language where their voice is not heard’) and a reading specified for the Reformation Day liturgy: the next verse of the same psalm: ‘Their sound has gone out into all lands; alleluia.’

God’s word and its spread was closely associated with the Reformation. In place of a gospel reading, the Reformation festival called for verses from the Book of Revelation, and they, too, take up this theme, ‘Then I saw an angel flying through the heavens, who had an eternal gospel to proclaim to those who live on earth, and all nations, tribes, languages and peoples.’ To Lutherans, the annual celebration of Reformation Day represented this proclamation of God’s word anew, and texts on this topic were especially appropriate.

Recurring themes

‘Gott, der Herr, ist Sonn und Schild’ was intended for Reformation Day from the start. Its festive scoring with two horns and drums reflect the high solemnity of the feast, and its opening psalm chorus of praise is also fitting. One of its arias refers explicitly to God’s word, the familiar Reformation topic, and promises praise ‘even though the enemy rages hard against us.’ This theme, the threat from enemies, appears several times in the cantata and relates to another Reformation Day topic: the vulnerability of the Lutheran Church, persecuted (in its view) by the Pope.

‘Ein feste Burg' might be Bach’s most famous cantata of all. It centres on Martin Luther’s hymn, whose four verses appear in the work in various musical guises. It, too, invokes the theme of protection from enemies. In fact this topic runs through the first three stanzas of the hymn, cast in military terms: a mighty fortress, weapons and arsenals, the field of battle, the defeat of the enemy.

This theme is reflected musically in two movements whose agitated violin lines were a conventional eighteenth-century emblem of battle—a musical representation of the way Lutherans saw themselves in the world.

The military topic of the cantata’s music was reinforced by Bach’s eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann, who made Latin-language adaptations of two chorale movements, not surprisingly for the celebration of a military victory. He added trumpets and drums to his father’s compositions; these instruments, which never had anything to do with Bach’s Reformation Day cantata, were mistakenly incorporated back into ‘Ein feste Burg’ in the nineteenth century, and this is the form in which the piece became famous.

Eighteenth-century Lutherans took careful note of Reformation anniversaries in part because confessional tensions were still in the air, even after two centuries. When Bach’s cantata 126 was heard in Leipzig at the 1755 commemoration of the Peace of Augsburg, its opening movement strikingly retained the original words of martin Luther’s hymn ‘Preserve us, Lord by your word / And control the murderousness of Pope and Turk.’

This was despite ecclesiastical instructions not to sing this or ‘Ein feste Burg’ at anniversary celebrations that year, in the hope that confessional strife might be kept to a minimum. But staunchly Lutheran Leipzig, ever wary, used Bach’s music to make a statement as it observed the anniversary of a central event of Luther’s Reformation.

-----

To find out about Oxford Bach Soloists, conducted by Tom Hammond-Davies,

go to: www.oxfordbachsoloists.com

For a 26-minute documentary on 'Singing the Reformation' directed by Dr Alex Lloyd, go to: https://youtu.be/XBsn4bAWpBY

Social media channels: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter @oxfordbach

-----

The late 14th century hymn which we know as 'Come down, O love Divine' by the Italian Jesuat Bianco de Siena (1367-1434), illustrates how the Holy Spirit kept alive a witness to Christ. In the centuries before the Reformation, while the church was at times mired in superstition and falsity, there was always a glimmer of light.

The hymn also shows how the Holy Spirit brings a gradual revelation of truth. There is a distinct yearning here, a hymn to the Spirit of Christ for the grace of Christ.

Come down, O Love divine,

seek thou this soul of mine,

and visit it with thine own ardour glowing;

O Comforter, draw near,

within my heart appear,

and kindle it, thy holy flame bestowing.

2 O let it freely burn,

till earthly passions turn

to dust and ashes in its heat consuming;

And let thy glorious light

shine ever on my sight,

and clothe me round, the while my path illuming.

3 And so the yearning strong,

with which the soul will long,

shall far outpass the power of human telling;

for none can guess its grace,

till he become the place

wherein the Holy Spirit makes his dwelling.

Translated by Richard Frederick Littledale (1833-1890)

We love to know what countries people are visiting from. By clicking 'That's fine by me' you agree to the use of cookies to help us see this info. (We see only the country names, with no personal details.) Thanks for your help. We value it.